BIG SCREEN SYMPOSIUM: KEYNOTE JANE HOLLAND: COSTUME DESIGNER Draft: 01 July 22

MANA AUAHA / CREATIVE POWER

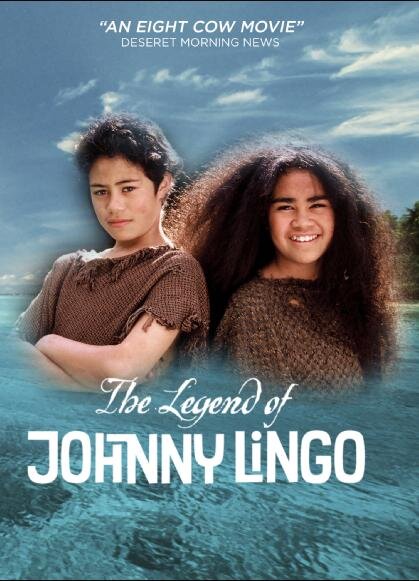

Slide sequence 1

Kiaora Tatau mā,

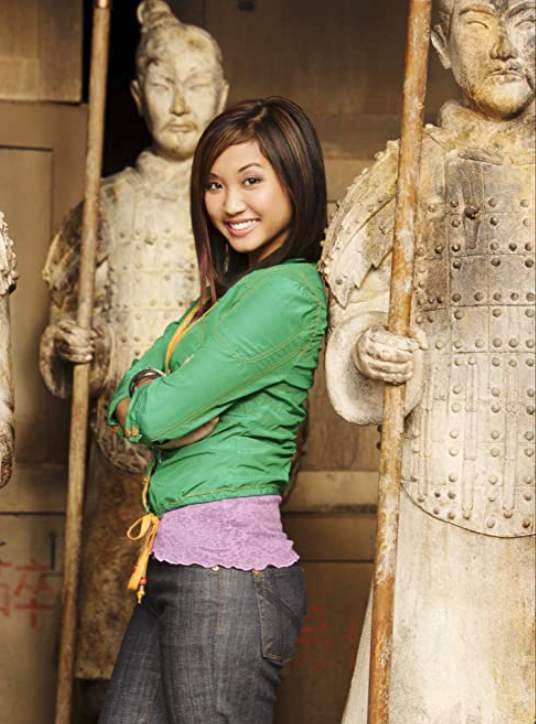

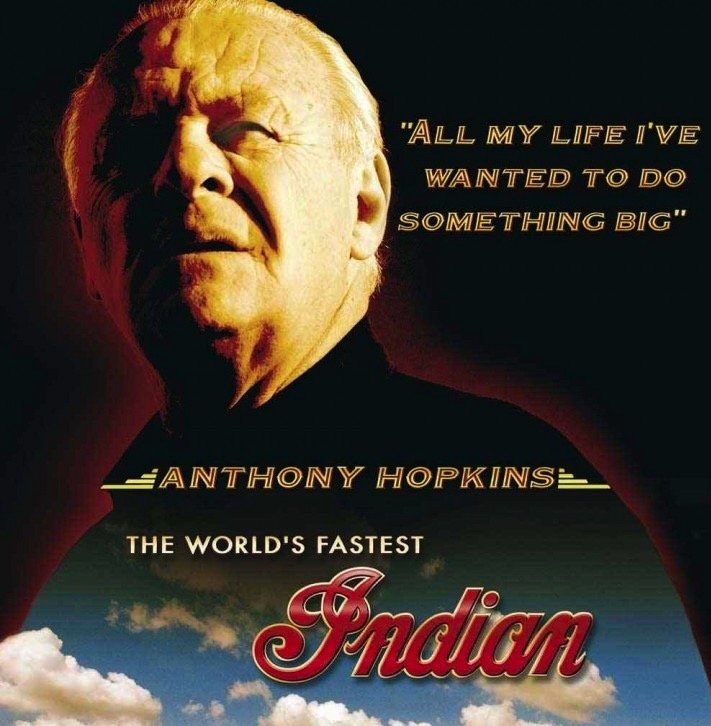

This film, World’s Fastest Indian was filmed in 2 halves – NZ & the US – and was made with 2 teams. I sent costumes to the US designer to fit on the lead character Burt Munro (played by Anthony Hopkins) because the US part was shot first. Some pieces made it to screen, some were sent back.

Slide sequence 2

When Anthony arrived in Invercargill, his wife Stella who was his support and his team really, told me he was all set costume-wise. Like many actors who come with a legacy, he really was no fuss.

Late in the shoot, the director suggested we change up a costume for the party scene. It meant a tight turnaround for the tailor, but it was Anthony Hopkins, after all and, the day before the scene, I fitted a 1960’s style suit. It was perfect.

I look good, he said ... And he did. He looked great...

...Maybe a little too good. What do you think?

He was right. But this was our only option other than the previously spec-ed costume. I talked it though with the director. He wanted Burt Munro to be scrubbed up for the scene and decided we could embrace the ‘too good’ as a movie-moment – the suit was approved.

I set about aging it, just to take the edge off ... but ‘a little too good’ was stuck in my head. I felt I needed a backup plan so I rang Strangely Normal, the tailor in Auckland, with a huge favour– to finish a suit that had come back from that first fitting months ago in LA.

It was a little quirky, inspired by a photo of Burt Munro. I knew it needed a bit of work.

We hatched a haphazard plan for Strangely Normal to work into the night, and then leave the suit in a wheelie bin outside their workshop for the courier to collect at 5am. By 10.30, I had the suit in Invercargill – I placed it at the back of the closet in Tony’s camper, behind everything. Just in case. And laid out the now aged ‘a little too good’ suit for him to dress.

He was ready... and happy... and then something happened.

I don’t know how he knew it was there, but he reached to the back of the closet and said, Why don’t I wear this one. Didn’t I try this in LA?

I said yes, but it was too heavy and not right... He said – well, it was so hot there, but now I’m here...

I really needed the director to be part of this conversation. He was a drive away on set and waiting for his actor.

I tried to stall. But it was too late...

... let me just try... the jacket was already going on... and then... in one of the great gifts of my career, Anthony Hopkins transformed right in front of me. He settled the jacket. He turned to the mirror... and said, “Hello Burt”.

Everything about costume design for me is encompassed in this moment. The difference between something that works and the magic of something that is just... right.

The tightrope of time and schedule and people.

The choices that make all the difference – the fabric imported from England – too heavy for LA, so appropriate for 1960s Invercargill.

The surprise of a peak lapel on a single-breasted jacket. The importance of fit... and context.

The collision of people and character.

Slide sequence 3

I describe my creative process as an agitation, in motion,

always looking to be additive to the collective story-telling process,

harvesting from the page,

running with the director’s vision,

massaging synchronicity with the production designer,

thinking about the interface with the cinematographer in tone and texture and play with light and feeding into hair and makeup for them to add their flair.

I work with aesthetic and authenticity and people. At the heart is character and the actor – how can I add to the visual expression of what makes them tick, what they shout about, what they hide and what lies just beneath the surface.

For all the thought, the ideas, the research, the aspiration behind world-building, I am nothing without my team.

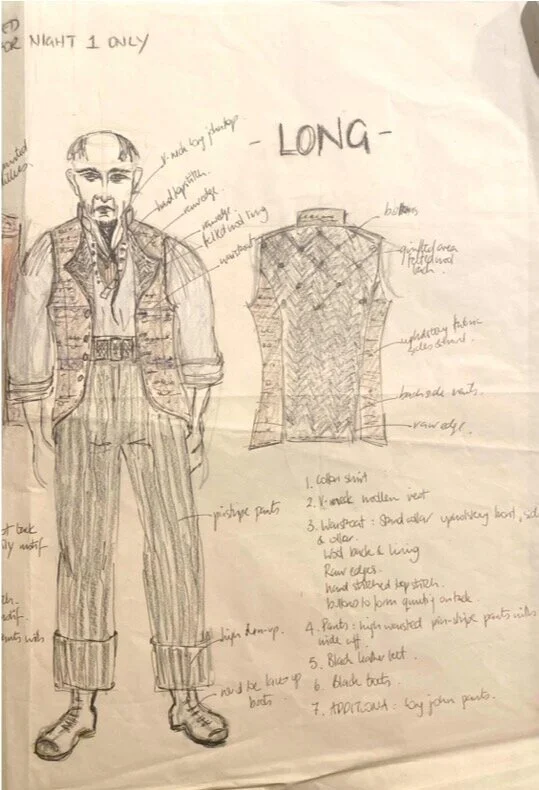

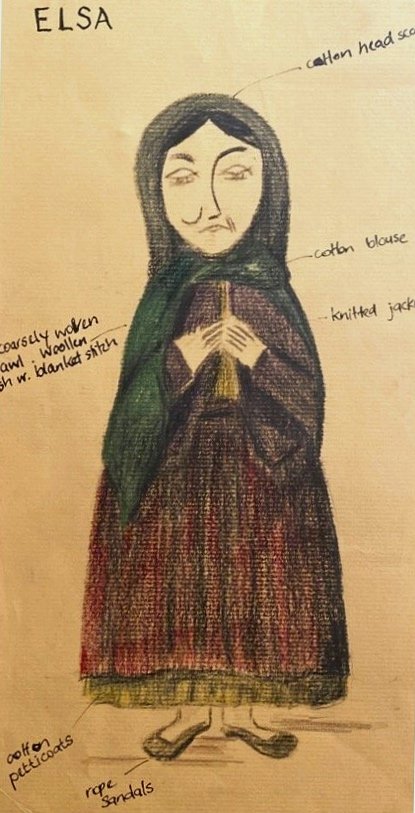

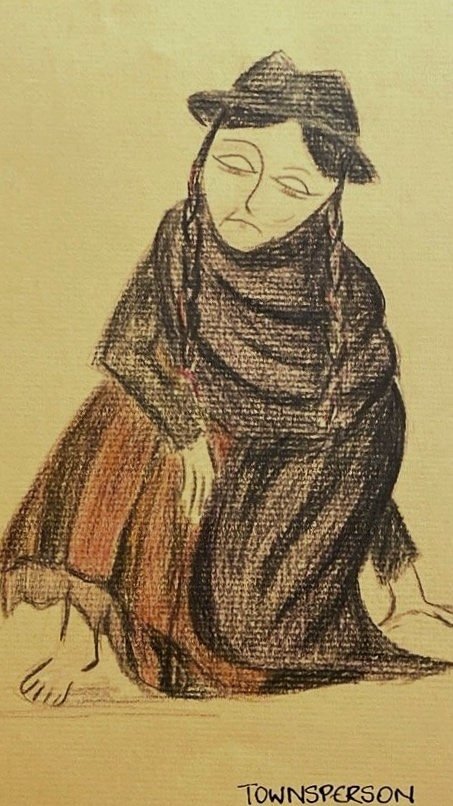

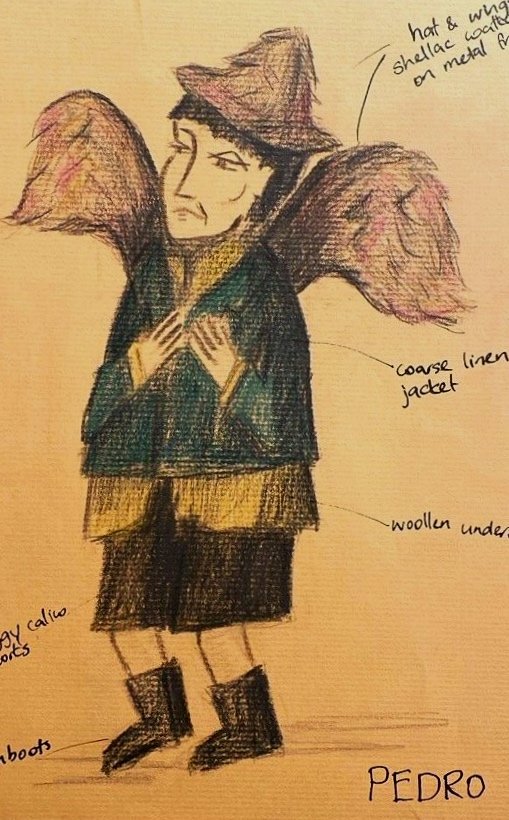

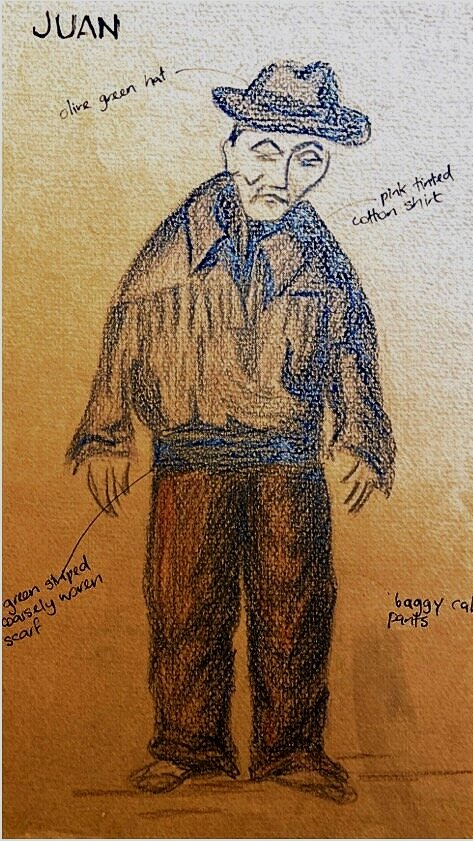

My happy place is the workroom. A world of highly specialised artisans who interpret a drawing into flat pattern pieces, then turn 2 dimensions into 3. Not only does a costume have to look good, but it has to function on a human body that moves in the most complex of ways, to stand the test of time, of action, weather conditions, the rigors of filming and to feel right.

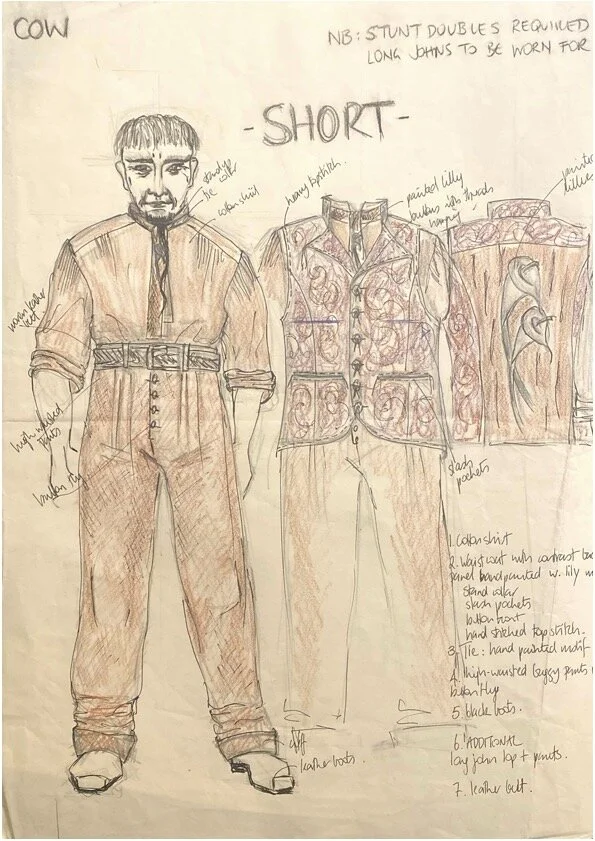

Slide sequence 4

The creative inquiry drills down, too...

What layers can I give an actor for storytelling possibilities ...

in the detail of a hand-made button,

the motif in a printed lining wrapping the character in a memory,

age and history worked into the folds.

Things that may or may not be seen on screen but add to the collective character voice. Often, when I’ve done my job well, our work is invisible. Costumes are embedded, belonging to characters and of their world.

Often our work is invisible.

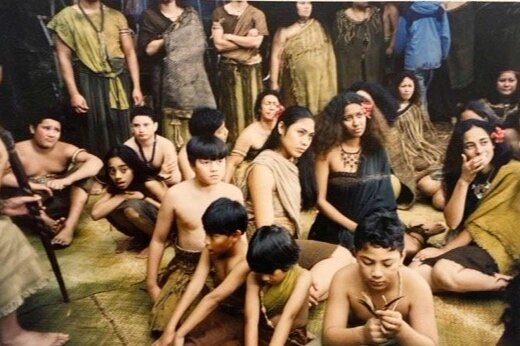

In these days when we are finally starting to embrace diversity on screen in a real and not gratuitous way, behind the scenes, the costume department is the lived-in embodiment of gender and cultural diversity. Pākeha cis-males barely exist.

Pretty much everyone has tertiary training, many with multiple degrees and post grad. Why? Because the work is multifaceted, technical, specialised and skilled. Yet, we are paid less than our counterparts in other departments.

Primarily because of, well, history ... we are a department of predominantly women.

But also, because often our work is invisible.

You see a row of women bent over sewing machines. It looks like factory work. Women’s work....

You don’t see the dance of their hands, the intricacy and exact nature of the work, the speed or the physicality of what they do.

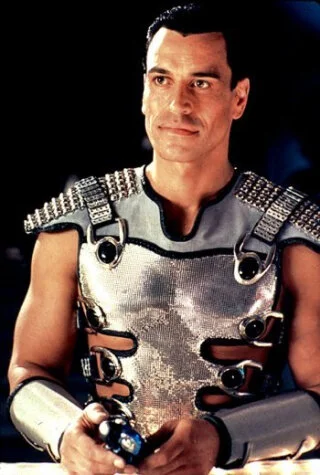

In a finished garment you don’t see how many individually calculated and sized pattern pieces make up a corset,

or register the complexity of sculpted pieces for articulated hand armour,

or have any idea how heavy fabric is when heaved between dye pots... or consider the science behind the colour in that dye pot.

Often our work is invisible yet, our visual impact on a show is crucial.

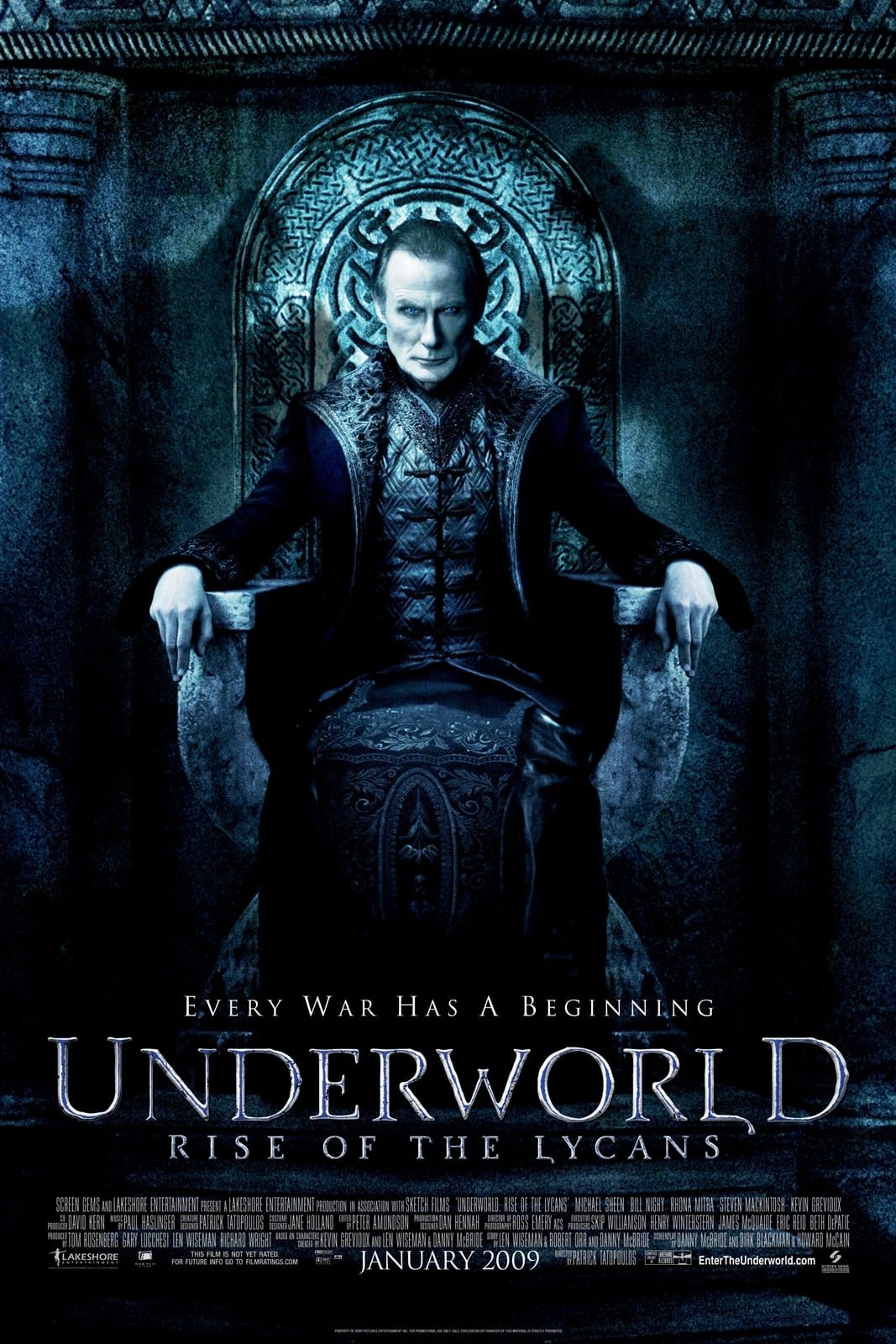

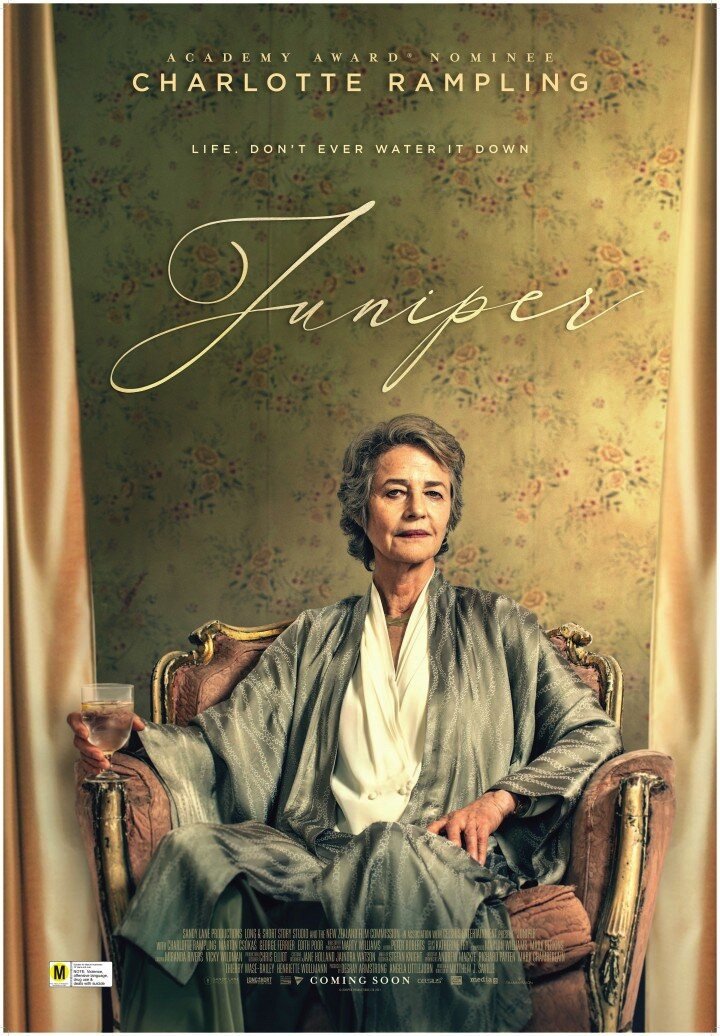

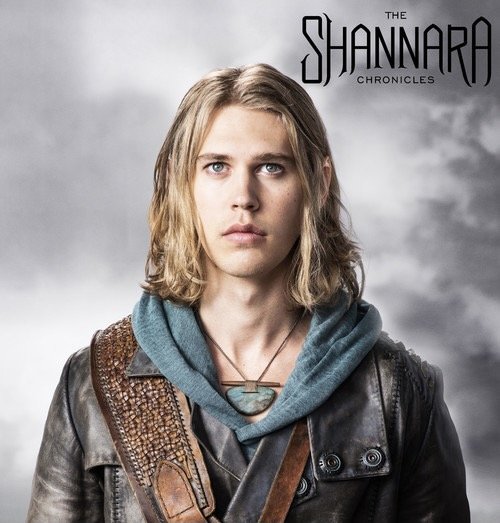

Slide sequence 5

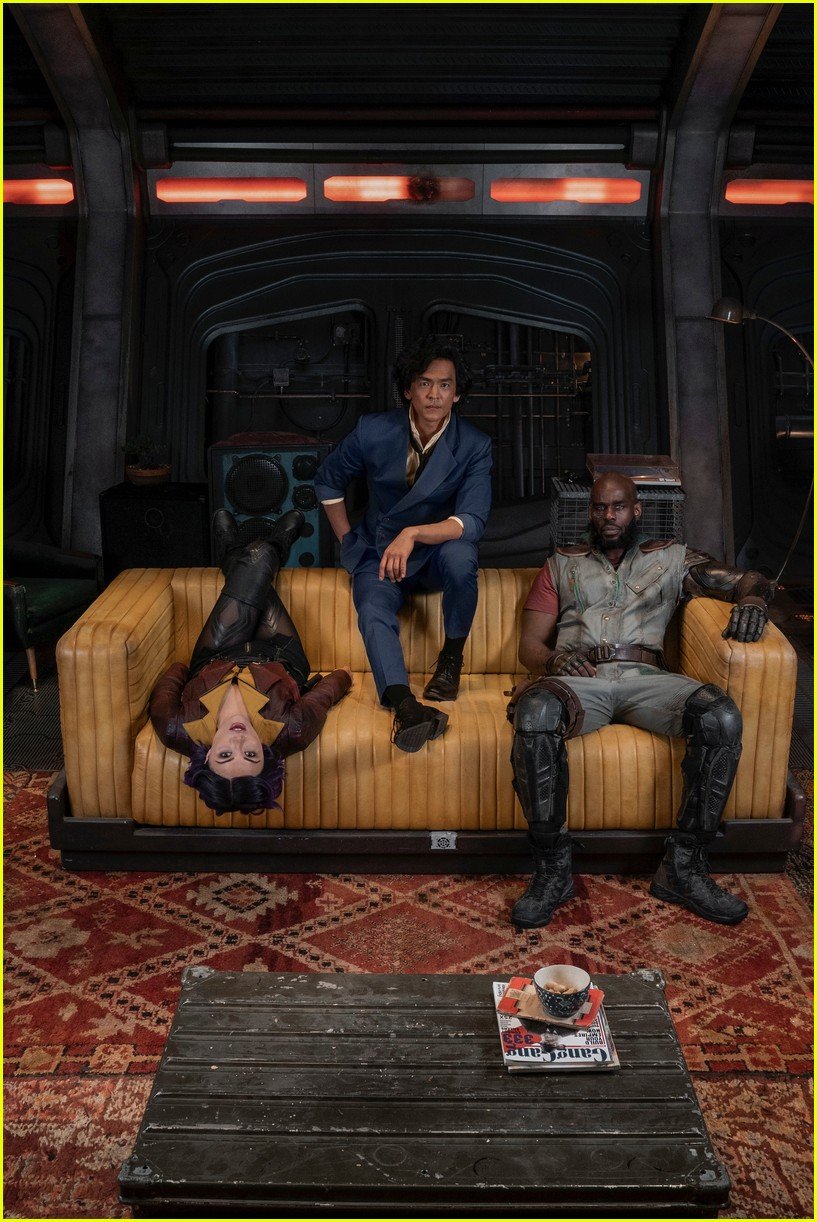

An actor in costume is often the world’s first taste of a show.

I will feel I have creative power when I know I am seen in the same way as my international counterparts, when my work is valued and therefore paid the same as other key creative HODs, and when I know the work my department does is valued for what it is and paid accordingly.

Mana and power are not the same. I have the feeling that if our industry worked from the space of Mana, issues such as visibility and parity wouldn’t even exist. Somehow Mana Auaha is more aspirational than Creative Power, and more accurately describes what we do –

Mana Auaha – expressive of that force within all of us creative beings to be additive to a collective vision on our quest for a moment of magic.

END

![Screen Shot 2017-10-20 at 11.47.44 AM [www.imagesplitter.net].jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b981bb65ffd20b0d6aef3f2/1537560899776-A738W2DQI5Z2RTAKZKDE/Screen+Shot+2017-10-20+at+11.47.44+AM+%5Bwww.imagesplitter.net%5D.jpeg)